How an artwork becomes a continuous learning process or: the case of the technological cyclops

One day around twilight at the Scheveningen beach, while the sun was setting in the horizon, we observed the number of people that reach out for their cameras to capture that precious moment. The colours, the warmth and the vanishing gleams on the sea are so alluring. In such a rapture, we cannot help ourselves, we need to seize the moment. The image captured however will never do justice to the magnitude of the scene. Yet, we insist on taking those pictures and even sharing them with the world, through our limitless connections.

At that very moment we started to wonder: what is this need? this instinct to capture, to store and to possess the sunset? Why are we always raptured? Does it touch something in our collective unconsciousness? Does it remind us of the passing of time, of our finitude? The phenomenon itself is of the order of the Sublime. It is cosmic, sensorial, metaphysical. First, we gaze at it through our embodied technology, our stereoscopic view, so to speak, of our eyes. But we quickly want to replace it with a flat representation, trying to grasp the massive phenomenon, by peeping through the small frame of the camera. In a flash, we realized that we turn ourselves into cyclops, or better said, technological cyclops. By looking through the viewfinder of the camera or into our tiny touchscreens, we lose depth, we don’t see anymore, we aim at a target. From being present, there with the sun, to a tele-presence, disembodying ourselves from the environment, right there at the seashore.

We then asked ourselves, how many pictures of the sunset are taken every day, every instant –right now as you read this– around the world? Where do all these pictures go? Why do we have this urge? And why can’t we take in the phenomenon with our senses? We then laughed and started toying with a foolish idea; what if we could freeze the moment? What if we would reenact the sunset with a physical thing, floating on water that would simply stay in place, whatever the weather conditions were? Would it slow us down and hold us from taking more and more pictures? Would it offer us a chance to be in the present?

We then began researching sunsets in art history, in films, in poetry. The sunset has been widely used to enhance a dramatic point of a story, translating feelings with visual contrast and melancholy. We also sketched our first collages of an artificial sunset, rendering a glowing dome on the water, under cloudy skies, and slightly off the horizon. Those first impressions showed also the potential to shift perspective; from the usual vanishing point to a closer relationship with the great star. This offered us a chance to speculate on the affective responses it could cause on the wider public.

Some time later, in early 2021, we were called by the founder of the Highlight Delft festival, Teun Verkerk, inviting us to create a new work with a large amount of LED panels. There was a strategic partner providing the equipment and we could propose anything we wanted. At that point it was still a joke to us, but we dropped the idea of reenacting a sunset in the canals of the idyllic town of Delft. We did not expect to realize it, neither did we knew how to make it. The project seemed impossible, even to the festival organizers. No one knew how to start it. Despite all the challenges of bringing this work to the world, Teun Verkerk took the chance to do it. It took him, and his team, months of negotiation with the city, the province and the water authorities. We had to gather all the minds we could, to research and tackle all the logistical details of the installation. Meanwhile, in our studio we were prototyping inflatable and experimenting with the LED panels to find that ideal dusk sensation (how naive were we to attempt to create a sunset?!). Of course, ideally, the work would be powered by solar energy, yes, of course. But that was a dream inside the dream.

One of the greatest serendipities in making Sunset in Delft was the fortunate location we chose for the installation. The location, as we’ve learned, is an essential aspect of the work. In Delft, we went for the Zuidkolk not only because it offered a good distance from the shore, with 360º chance of view; but it also coincided with Vermeer’s ‘View of Delft’ (c. 1666), one of the few outdoor scenes of the Golden Age master. As a contemporary man of his time, Vermeer was aware of the latest developments in Optics. Not far from his studio, in the same prosperous era, other pioneers were experimenting with scientific tools, such as Anthoni van Leeuwenhoek, who was polishing glass lenses that resulted into the first microscopes in history; while Christiaan Huygens, in Voorburg, was exploring the first telescope[1]. With high probability Vermeer himself used optical devices to assist his painting process[2] and capture light as no one else. His use of the camera lucida allowed him to visualize the subject matter in a controlled manner, through which he could peep and develop his pictures from. While Vermeer is known for stunning interior pictures, this single landscape painting, ‘View of Delft’ is also a testimony of the latest developments in Optics. We saw this painting as an important link in our investigation into image production. If today we can’t seem to attend a memorable event without taking the maximum number of photos, could our work ever entice a technology-free sense of presence?

To illustrate this anecdote we made a collage, digitally pasting our artificial sun onto Vermeer’s painting. We framed it and offered it as a gift to the Delft’s Water Authorities. Legend has it that this tongue-in-cheek collage was the turning point for the festival to obtain the permit needed for our Sunset to be installed in the Zuidkolk junction. And we got it. It’s astonishing to see the old ships seen in this stunning painting have been replaced today by uncomparable colossal ships that cross the idyllic canals of Delft.

After months of intense planning, problem solving and worrying, on the night of 18th November 2021 Sunset in Delft had a quiet premiere. Struck by the second COVID lockdown, the festival had to be postponed, and only the Sunset could carry on, as an outdoor piece. We couldn’t however make any public announcements other than modest invitations to friends and partners of Highlight Delft. The temporary health restrictions required that the installation would not constitute a “public event”, along with all the events canceled around the country. The only visitors who came were indeed a small network of folks who knew about the work. Casual passersby, mostly inhabitants of Delft, were probably flabbergasted. They couldn’t even grasp what actually was that glowing dome on the water, for three consecutive nights. Although a small poster was placed on the sidewalk then, stories and hearsay emerged, as little was known about it.

One news channel, the Algemene Dagblad, did some coverage of Sunset in Delft. And later in January 2022, the local paper ‘Zicht op Delftzicht’ published an article recapping it. Due to its brief appearance, the work however went mostly unnoticed, until someone would reach out again for a new installment. What we’ve learned then, was that an artwork installed in public space lifts off and lives its own life. It absorbs many new meanings given by passersby and the urban context. One nearby dweller for instance told us that people were talking about UFO’s. Another one told us that it had a personal significance in a very harsh time for their family. Anyone could make up their own story and we loved it.

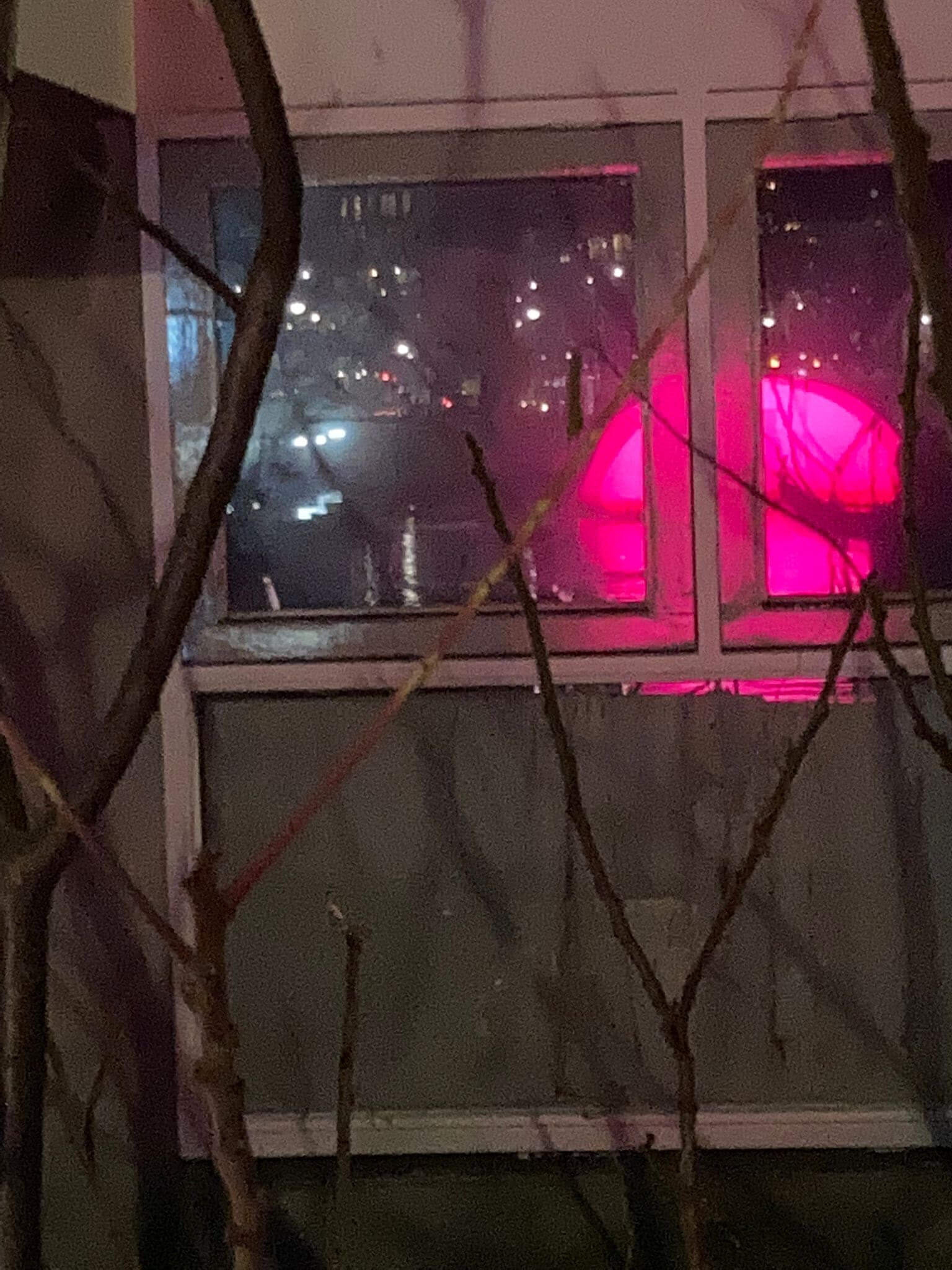

Soon enough, we started receiving emails from strangers, who, living in Delft and hearing about the artwork, decided to share their pictures with us. There were photos from the most unexpected points of view, from the living rooms of our visitors. Unknowingly, we were initiating an archive of an artificial Sunset, a crowdsourced project which we could not have anticipated.

It was only after the work had been installed, and seen in its full scale, that we realized the consequences of our idea. Besides all the stress and physical labor, of hours with our hands in the cold water, turning it on and off every night; there was a lot more to learn than we could have expected. Once in public space, the work belonged to the world. It was subjected to harsh weather conditions and potentially to vandalism, but the most exciting aspect was the fact that it perfectly belonged to the place. The panoramic perspective became an invitation to walk around, and to discover the place as if it were new. The project thus had much larger consequences than we had imagined. The fact that people wanted to share their Sunset photos with us also requires us to grapple again with the very issue of image production. We are still processing this secondary project that became the archive –pondering between publishing a book or a website where these images can be made public again. The irony of the work’s inception turned against us; precisely that question on how many pictures we, as humanity, can make of the sunset every day is still buzzing.

During that brief first edition of the Sunset in Delft, Ludmila was also collaborating with choreographer Marina Mascarell, in the role of stage designer. This collaboration resulted in the dance piece ‘How to cope with a sunset when the horizon[1] has been dismantled’, produced by NDT, the Nederlands Dans Theater, in early 2022. The fact that the horizon had vanished in Sunset in Delft was another fortunate surprise. What happens when boundaries collapse and there’s no parameter for that distant line that separates us from the skies? In hindsight, the work is also about proximity. In many of Ludmila’s works, proximity, and tactility, play a major role in the audience’s experience. Rather than privileging vision, she tries to remind the public of our “other senses”. Despite Sunset being placed at about 40 meters away from the viewers, and therefore being mainly seen, the work also evokes a break in distance, suggesting a haptic relationship with the city. It incites the public to wander around and find different angles to see with their bodies in motion. With the offset of the horizon, a new relationship with the urban environment arises.

In the following months we were invited to show the work in our hometown The Hague, in no less than the privileged location of the Hofvijver –at the heart of the Dutch national government. Among the significant institutions in the area, there is the Mauritshuis, incidentally the museum where ‘View of Delft’ is displayed along with other renowned paintings from the Dutch Golden Age. Sunset in The Hague was installed just a few meters away from Vermeer’s landscape, echoing our first edition, but now right by the prime minister’s windows. As part of a new event called ‘BlowUp Art The Hague’, the work saw its first glory being exhibited through four nights, including one buzzy Museum Night and, this time, with no health restrictions. Once again we received a ton of pictures from the public. Once again the work gained new meanings in this unique context of The Hague’s city. Some visitors saw it as a critique on the inept national government, others interpreted it as a commentary on global warming. One tipsy passerby, late at night, after many drinks, asked us to define what that glowing object in fact was – a question which we preferred to leave open and ask him back what he was seeing. It startles us sometimes the fact that some visitors might expect defined meanings to something they can perceive with their very senses. It feels as though they cannot believe their eyes and demand an explanation for that strange image. Birds and ducks, on the other hand, seemed to accept our installation as the most banal thing happening in their surroundings.

In 2023 came the opportunity to set the sun in Paris, during the explosive Nuit Blanche, an event that gathers crowds throughout the whole city, from 6PM to 6AM. Again we had the privilege to choose the best spot, scouted by a fabulous team of curators, producers and technical coordinators. We took the Île de Saint Louis as it offered diverse perspectives, from either side of the river Seine and from the iconic Parisian bridges[1]. This single night show gathered thousands of revellers around our installation, in a nigh-long delirium. After Sunset in Paris, came Sunset in The Woods, a month-long edition in the suburbs of Paris. This show took place in the pristine pond by the Hangar Y. During that winter, our Sunset endured the lowest temperatures ever, being covered in ice on its final days of exhibition.

The most recent edition took place in Amsterdam, 2025, within the program (Un)monumenting by NDSM, curated by Petra Heck. The five-week show was a whole new proposal defying the weather and the rough waters of the river IJ. Placed in the fast changing harbor, Sunset entered in conversation with the latest urban developments of the northern part of Amsterdam, leaving the touristic image of the city behind. While being installed in one of the most photogenic cities of Europe, the Sunset was placed at its edge, one teeming with cranes and modern towers, pointing at an era that most tourists don’t see. As an agent of remembrance and imagination of urban futures, NDSM put into question what a monument is and can be, a proposition that resonates with the notion of radical heritage[1] proposed by Erik Rietveld and Ronald Rietveld.

New editions of the artwork are yet to be confirmed –we are in constant conversation with parties from diverse locations. We ourselves also have our dream spots too, Tromsø, São Paulo, Rio, Locarno, Shanghai and so forth. Every edition of Sunset has proven to be a challenge in itself and therefore always a learning process involving endless dialogue among all collaborators and stakeholders. In each case, adjustments and solutions had to be studied specifically to fit the situation, respecting the local regulations etc. Water bodies are often protected as heritage. Equipment and (wo)manpower needed to be recalculated case by case. Flying drones for visual documentation is often forbidden. This myriad of challenges renders the artwork into a new project every time. And above all, each place provides its own character, forming a new context for the sun to set in, a new story of the Sunset. At times placed closer to the shore, other times better seen by boat, suspended and swaying at a distance, against the cloudy sky. Does our Sunset warm people’s imagination? What does it do when you stare at the warm hues during the cold winter evenings? Does it slow one down to walk and take a chance to reflect on the fast-pace of our lives? In the experience of encountering our buoyant Sunset, visitors have discovered new spots which they had never noticed before. They go under bridges, behind fences, look in-between spaces to find light from different angles. In doing so, our relation with the city becomes more imaginative, finding play and zest in the ordinary.

Ludmila Rodrigues and Mike Rijnierse, June 2025

We are grateful for different partners and supporters, Teun Verkerk, Toon Kennedy, Mary Hessing, Remco Schuurbiers, Kitty Hartl, Petra Heck and many others.

[1] https://www.esa.int/esapub/sp/sp1278/sp1278p1.pdf

[2] See David Hockney’s ‘Secret Knowledge’ and Tim Jenison’s documentary ‘Tim’s Vermeer’.

[3] Our other option would be to place it by the Notre Dame Cathedral which would have been epic, had the church not been under construction then, after the 2019 fire. The 24-hour working shifts of restoration would damage our Sunset in Paris postcard, sprinkled with bright light spots in the background.

[4] See Hardcore Heritage: Imagination for Preservation, Erik Rietveld and Ronald Rietveld, 2017: https://www.raaaf.nl/en/projects/1005_delta_work_m1611